AI chips are larger than the smartphone processors and so more likely to be defective due to production errors. According to a source familiar with the production side, the current yield rate of Huawei’s Ascend 910 b chips is only just over 20 percent, meaning almost four out of every five chips produced are defective.

SMIC’s production expansion is expected to encounter greater difficulties than three years ago due to restrictions imposed by the US, Japan, and the Netherlands. The most advanced of ASML’s DUV machines, which SMIC used for both developed and older chips, were included in the Dutch and US export controls.

ASML said it “complies with all applicable export controls rules and regulations” and that its customers are aware that, from 2024, it is “unlikely we will receive export licenses for these systems for shipment to domestic Chinese customers.”

But SMIC’s suppliers say the company received a new batch of advanced DUVs from ASML before the US tightened export controls, meaning a ramp-up in production and technology development is still possible over the next two to three years.

“Much of the equipment here is still American and Japanese products that SMIC stocked up in 2020,” one of the people says.

However, industry experts and analysts believe SMIC might run out of equipment maintenance and material supplies before it can manufacture advanced chips.

“Some stockpiles of machine parts will run out in two to three years, with no replacements from homegrown companies and a minimal share of purchases through the black market,” says Leslie Wu, an independent consultant on China’s semiconductor industry.

“There is no proper answer to the components restrictions,” he says. “This would be a huge trouble . . . [if] the stockpiled pieces run out before the domestic alternative appeared.” Huawei and SMIC did not reply to requests for comment.

National champions

Both Huawei and SMIC can at least be sure of state support as they attempt to keep up with industry leaders. A government official in semiconductor industry policymaking says the current objective is to establish production lines for cutting-edge chips “at all costs.”

“A stable chip supply chain is the backbone of high-performance computing systems... crucial for China’s high-performance computing industry to maintain its development momentum, especially with ongoing trade tensions and restrictions imposed by the US government,” the official says.

Starting with the establishment of the China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund in 2014, Beijing has nurtured its microchip industry with state funding. The investment fund has amassed a whopping $47 billion over the past decade and is projected to raise an additional $41 billion, further bolstering China’s quest for technological self-sufficiency.

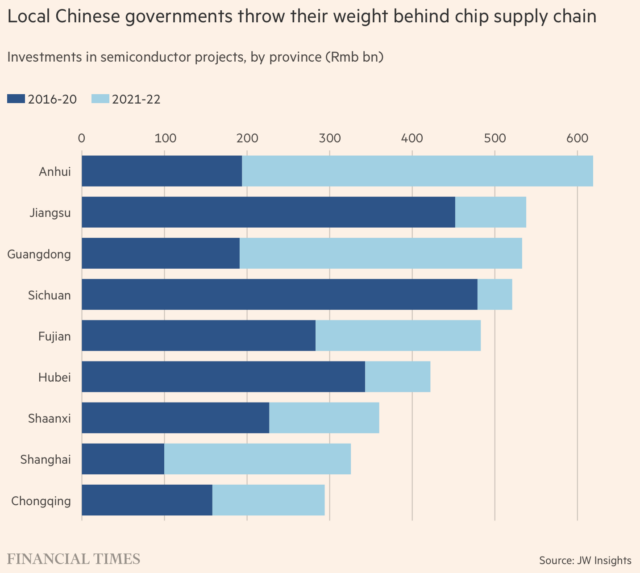

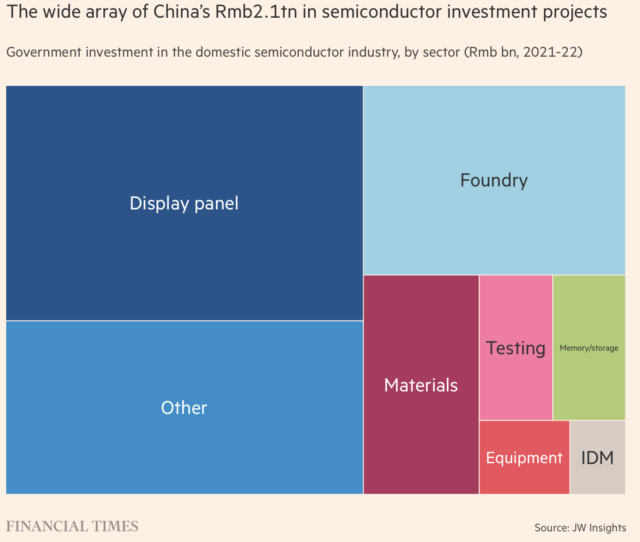

A report by research firm JW Insights, which analyzed governmental investment by 25 provinces and regions, revealed that the government had poured $290.8 billion into semiconductor-related sectors in 2021 and 2022, with one-third going to semiconductor equipment and materials.

The rationale behind this massive investment is simple: break free from heavy reliance on imports, gain a stronger foothold in the global supply chain, and take away the US ability to switch off a considerable portion of China’s industrial and defense economies.

“If you import most of your chips, you’re not a manufacturing superpower,” says Chris Miller, author of Chip War. “You’re just assembling high-value components produced elsewhere.”

The Chinese State Security Ministry seemingly agrees, writing on its WeChat account: “Only by holding core technologies in our own hands can we truly take the initiative in competition and development, and fundamentally ensure national security, in economy, defense and more.”

This ambition to escape dependence on foreign technology rests on the shoulders of Huawei and SMIC. The successful launch of the Kirin 9000S injected new vigor into the semiconductor industry, with executives reporting that chip start-ups are seeing a surge in funding.

But Huawei’s long-term ambitions are not limited to the markets in China’s orbit. The original nickname for the Kirin 9000S—Charlotte—is a symbol of these hopes. It was named not for an individual, but for the city in North Carolina. Other mobile semiconductors in development are also named internally for US cities, insiders say.

Using American names, says one Huawei employee, reflects “our desire to one day reclaim our place in the global supply chain.”

© 2023 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.

reader comments

197