Easy-to-exploit flaw can give hackers passwords and cryptographic keys to vulnerable servers.

See full article...

See full article...

Slow clap bravo. Chefs kissown[ed]Cloud

A cursory look says no, but I'd keep an eye on their security-advisories pageDoes Nextcloud have the same problem?

That was my first thought also.Does Nextcloud have the same problem?

Exactly my first thought. Bravo!own[ed]Cloud

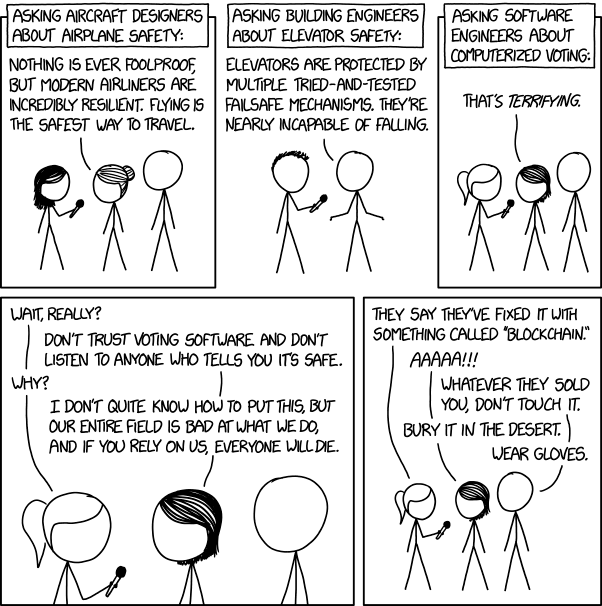

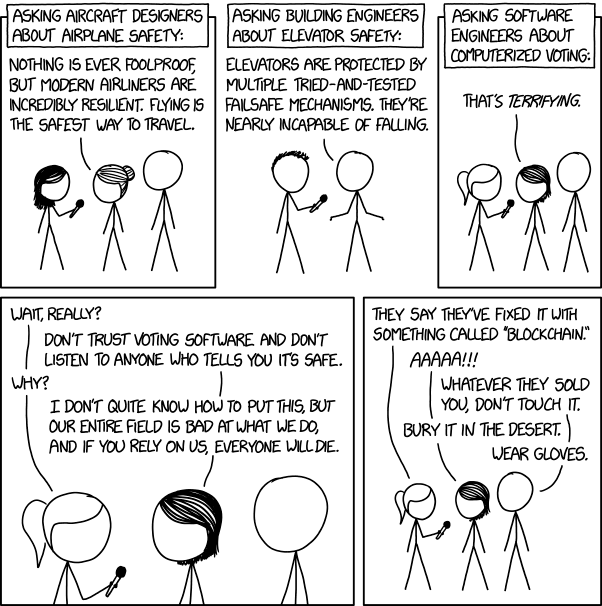

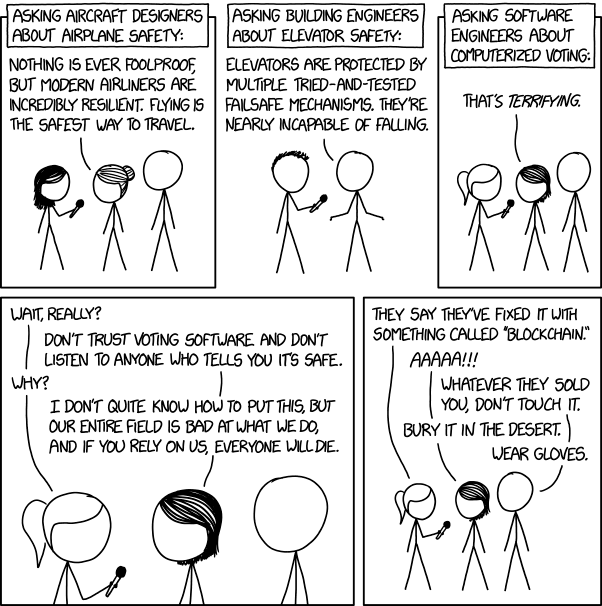

Even more so, given that the tragic MCAS issue was a software engineering problem -- granted, it had been implemented to hide a number of hardware design and logical problems that would never have been allowed to fly in a sane airplane but for regulatory capture, but still... it's software bugs all the way down.I have been doing code review and pen testing for years and the amount of dumbshittery I see is insane. This XKCD is really right: The entire IT industry sucks at what it does.

And given the advent of the 737 Max and MCAS, it is especially ironic.

All open source package managers I've seen are pretty much exactly this mess of dependencies. It's a pretty big and common issue unfortunately.So using a 3rd party api that uses a different 3rd party library might not be the best security practice?

My cursory reading of the article and the CVE would confirm that yes, you would be protected if OwnCloud was not facing the internet. E.g., accessible only to clients/users through a VPN, and not exposed directly to the internet.I assume that instances protected by Cloudflare Tunnels or some other zero trust proxy would prevent these attacks? Or is that wishful thinking?

I assume that instances protected by Cloudflare Tunnels or some other zero trust proxy would prevent these attacks? Or is that wishful thinking?

This xkcd also seems appropriate.I recently got a notice from a life insurance broker I had never heard of that they had lost all of my info in the MOVEit vulnerability. I wouldn't be surprised if someone lost it in this one too. Since I am in every other breach, my credit reports have been frozen for years.

I have been doing code review and pen testing for years and the amount of dumbshittery I see is insane. This XKCD is really right: The entire IT industry sucks at what it does.

And given the advent of the 737 Max and MCAS, it is especially ironic.

What? Do you think that commercially run cloud operators got barrels of magic pixie dust or something to sprinkle on their systems to keep them safe and secure?"I will simply operate my own cloud" has always been a deeply stupid meme that severely underestimates the effort and attention required to run hardware and software safely. Umpteenth example.

I apologize, but this Disney-vilification is oversimplifying the issues at play with the 737MAX, which bothers me enough that I am going to write a comment on the internet.Even more so, given that the tragic MCAS issue was a software engineering problem -- granted, it had been implemented to hide a number of hardware design and logical problems that would never have been allowed to fly in a sane airplane but for regulatory capture, but still... it's software bugs all the way down.

Am I missing something, or is that a massive WTF?these environment variables may include sensitive data such as the ownCloud admin password, mail server credentials, and license key

This is off-topic, but I'll respond briefly. I think a lot of what you're saying is true, but I disagree with assigning any blame to pilot error. What I've read (see below especially) indicates the pilots were responding as they were trained.I apologize, but this Disney-vilification is oversimplifying the issues at play with the 737MAX, which bothers me enough that I am going to write a comment on the internet.

The crashes of the 737MAX touch on a multitude of problems: software engineering is one, but also, bureaucracy, politics, and training. Especially in modern aviation, there is no root cause, and these crashes were no exception. (For those unaware: In the span of a couple weeks, two brand-new fully-loaded 737MAX airframes crashed, killing all aboard.) The purpose of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, was to make the 737MAX airframes behave like earlier-model 737s, which meant that no additional training was required for pilots to transfer from the 737 Next Generation airframes. Airlines wanted this, because it reduced their costs, and Boeing wanted it because it made use of a sort of network effect. Airlines who were already flying the 737s, with the massive pool of pilots trained on them, would be less likely to purchase an AirBus 321neo and incur the training costs.

However, as has been widely reported, MCAS had a flaw. If the Angle of Attack (AoA) values were incorrect, it could attempt to compensate and trim the aircraft nose-down. Under normal circumstances, this did exactly what it should have— made the 737MAX fly like the older 737NGs. If the AoA sensor data was wrong, it would never report that the aircraft was flying horizontally, and MCAS would continue to input more and more nose-down pitch. This is something the FAA should have caught, but didn't, because it has been so gutted by politicians that manufacturers perform self-certification of many things, which the FAA is too understaffed to even check those. MCAS both pitched down too much, and too many times, and that is the software flaw. It is also the easy Disney villain of this story, and that's why everyone points at it, but just waving our hands and going "oh, it's software!" is not doing justice to the over 300 dead people. Let's try and do better by them— because even though MCAS had this fault, other factors should have prevented these crashes. Let's talk about politics, bureaucracy, and training.

Most aircraft systems are doubly-redundant, if not triply- or quadruply-redundant. Indeed, the 737MAX has two AoA sensors, which independently feed the displays used by the pilots. So why did MCAS use just the AoA data from the captain's side, so a single failed sensor could cause these unending nose-down inputs? In short: that's how it was ordered. And here is where we need to discuss Lion Air.

Lion Air was chosen by Boeing to be the launch partner for the 737MAX. They ordered a ton of brand-new 737MAX airframes, and their 2018 launch was going to be spectacular. This was a spectacular windfall for Boeing, especially after the merger with McDonald-Douglas, wherein the MBA zombies from the latter company essentially ate the former, turning Boeing from an engineering company into a short-sighted profit-seeking entity. It's a sad sight to see, but that discussion is an even further digression from this digression, so we'll skip it for now. Anyway.

Lion Air had also been barred from flying in the EU up until mid-2016. In fact, when Lion Air agreed to purchase the 737MAX, they weren't allowed to fly in the EU! Some travel advice: never fly on an air carrier banned from operating in the EU. So Boeing had sold their brand-new aircraft, and was going to launch it on an airline that was banned from operating in the EU market. Only a couple years passed between the EU lifting the ban of Lion Air and the 737MAX crashes. When Lion Air ordered these airframes, they opted to not include an AoA disagreement warning light. There was internal discussion at Boeing... but eventually, the customer is always right, even if they shouldn't be, and they sold them the aircraft they wanted. Later, as Boing test pilots were training Lion Air pilots, they wrote memos and documented numerous failures of those pilots to handle situations they considered safety-critical.

If your flying scares a test pilot, it's not a good sign. But nonetheless, Boeing's inertia was in play, and damnit, they were going to sell a lot of airplanes. So the test pilot's reports were stuffed into a folder, and the sales continued, and the launch partnership progressed. Even if MCAS had its faults, the failure mode it presents as is something called "trim runaway". It is exactly what it sounds like— the aircraft trimming is not working, and is going nose-low or nose-high, and the pilots have to push on the yoke to correct it. This can take a huge amount of force. Somewhat recently, an acquaintance-of-a-friend had a trim runaway situation in his airplane on short final, about 400 feet above the ground when coming in for a landing. (It is too small of an airplane to have a flight data recorder, but my impression was he forgot to aviate before navigating or communicating. He made a radio call, but that didn't leave enough time to respond to the emergency.) He crashed and died just short of the runway. Trim runaway is a common-enough problem that pilots are trained for it and must respond quickly. The Lion Air pilots, as per Boeing's own pilot's documentation, were not good pilots. There is serious evidence they cheated on simulators, knowing how to take the test as it were instead of knowing why the answers are correct. Thus, when presented with a trim runaway situation in the real world, they constantly tried re-engaging the autopilot instead of hitting the trim cutout tabs and hand-flying the airplane.

Ultimately, pointing at MCAS and saying it is a software problem is wrong. Likewise, pointing at the pilots and saying they failed is also wrong. This was a very complex problem, and it required poor quality pilots, bad software, corporate ineptitude, dodgy companies selling pencil-whipped AoA sensors, and more to manifest itself. And, sadly it did— twice in a very short period of time.

And, yes, software sucks. The discipline of software engineering could learn a lot from its real-world counterparts (aviation, despite its flaws, included) and the world would be a better place. Sorry if this is a weird tangent, I don't have an owncloud instance to patch, but looking at the aviation industry's response to these situations is somewhat hopeful, even if each lesson-learnt is tragically written in blood. Software engineering can't even manage to learn from coding mistakes that resulted in death (Therac-25) or, worse for capitalists, the loss of money.

I would like to subscribe to your newsletter. Seriously.I apologize, but this Disney-vilification is oversimplifying the issues at play with the 737MAX, which bothers me enough that I am going to write a comment on the internet.

The crashes of the 737MAX touch on a multitude of problems: software engineering is one, but also, bureaucracy, politics, and training. Especially in modern aviation, there is no root cause, and these crashes were no exception. (For those unaware: In the span of a couple weeks, two brand-new fully-loaded 737MAX airframes crashed, killing all aboard.) The purpose of the Maneuvering Characteristics Augmentation System, or MCAS, was to make the 737MAX airframes behave like earlier-model 737s, which meant that no additional training was required for pilots to transfer from the 737 Next Generation airframes. Airlines wanted this, because it reduced their costs, and Boeing wanted it because it made use of a sort of network effect. Airlines who were already flying the 737s, with the massive pool of pilots trained on them, would be less likely to purchase an AirBus 321neo and incur the training costs.

However, as has been widely reported, MCAS had a flaw. If the Angle of Attack (AoA) values were incorrect, it could attempt to compensate and trim the aircraft nose-down. Under normal circumstances, this did exactly what it should have— made the 737MAX fly like the older 737NGs. If the AoA sensor data was wrong, it would never report that the aircraft was flying horizontally, and MCAS would continue to input more and more nose-down pitch. This is something the FAA should have caught, but didn't, because it has been so gutted by politicians that manufacturers perform self-certification of many things, which the FAA is too understaffed to even check those. MCAS both pitched down too much, and too many times, and that is the software flaw. It is also the easy Disney villain of this story, and that's why everyone points at it, but just waving our hands and going "oh, it's software!" is not doing justice to the over 300 dead people. Let's try and do better by them— because even though MCAS had this fault, other factors should have prevented these crashes. Let's talk about politics, bureaucracy, and training.

Most aircraft systems are doubly-redundant, if not triply- or quadruply-redundant. Indeed, the 737MAX has two AoA sensors, which independently feed the displays used by the pilots. So why did MCAS use just the AoA data from the captain's side, so a single failed sensor could cause these unending nose-down inputs? In short: that's how it was ordered. And here is where we need to discuss Lion Air.

Lion Air was chosen by Boeing to be the launch partner for the 737MAX. They ordered a ton of brand-new 737MAX airframes, and their 2018 launch was going to be spectacular. This was a spectacular windfall for Boeing, especially after the merger with McDonald-Douglas, wherein the MBA zombies from the latter company essentially ate the former, turning Boeing from an engineering company into a short-sighted profit-seeking entity. It's a sad sight to see, but that discussion is an even further digression from this digression, so we'll skip it for now. Anyway.

Lion Air had also been barred from flying in the EU up until mid-2016. In fact, when Lion Air agreed to purchase the 737MAX, they weren't allowed to fly in the EU! Some travel advice: never fly on an air carrier banned from operating in the EU. So Boeing had sold their brand-new aircraft, and was going to launch it on an airline that was banned from operating in the EU market. Only a couple years passed between the EU lifting the ban of Lion Air and the 737MAX crashes. When Lion Air ordered these airframes, they opted to not include an AoA disagreement warning light. There was internal discussion at Boeing... but eventually, the customer is always right, even if they shouldn't be, and they sold them the aircraft they wanted. Later, as Boing test pilots were training Lion Air pilots, they wrote memos and documented numerous failures of those pilots to handle situations they considered safety-critical.

If your flying scares a test pilot, it's not a good sign. But nonetheless, Boeing's inertia was in play, and damnit, they were going to sell a lot of airplanes. So the test pilot's reports were stuffed into a folder, and the sales continued, and the launch partnership progressed. Even if MCAS had its faults, the failure mode it presents as is something called "trim runaway". It is exactly what it sounds like— the aircraft trimming is not working, and is going nose-low or nose-high, and the pilots have to push on the yoke to correct it. This can take a huge amount of force. Somewhat recently, an acquaintance-of-a-friend had a trim runaway situation in his airplane on short final, about 400 feet above the ground when coming in for a landing. (It is too small of an airplane to have a flight data recorder, but my impression was he forgot to aviate before navigating or communicating. He made a radio call, but that didn't leave enough time to respond to the emergency.) He crashed and died just short of the runway. Trim runaway is a common-enough problem that pilots are trained for it and must respond quickly. The Lion Air pilots, as per Boeing's own pilot's documentation, were not good pilots. There is serious evidence they cheated on simulators, knowing how to take the test as it were instead of knowing why the answers are correct. Thus, when presented with a trim runaway situation in the real world, they constantly tried re-engaging the autopilot instead of hitting the trim cutout tabs and hand-flying the airplane.

Ultimately, pointing at MCAS and saying it is a software problem is wrong. Likewise, pointing at the pilots and saying they failed is also wrong. This was a very complex problem, and it required poor quality pilots, bad software, corporate ineptitude, dodgy companies selling pencil-whipped AoA sensors, and more to manifest itself. And, sadly it did— twice in a very short period of time.

And, yes, software sucks. The discipline of software engineering could learn a lot from its real-world counterparts (aviation, despite its flaws, included) and the world would be a better place. Sorry if this is a weird tangent, I don't have an owncloud instance to patch, but looking at the aviation industry's response to these situations is somewhat hopeful, even if each lesson-learnt is tragically written in blood. Software engineering can't even manage to learn from coding mistakes that resulted in death (Therac-25) or, worse for capitalists, the loss of money.

Thank you - that was one of the most insightful comments I've read on Ars, or anywhere for that matter, in quite a while.I apologize, but this Disney-vilification is oversimplifying the issues at play with the 737MAX, which bothers me enough that I am going to write a comment on the internet.

these environment variables may include sensitive data such as the ownCloud admin password, mail server credentials, and license key

This hits containerized deployments especially hard, and in those environments all the infrastructure is spun up from scratch.Am I missing something, or is that a massive WTF?

phpinfo enabled, aka "tell me everything about the running environment" is poor form, to say the least.This has to be a pretty strange set of circumstances that produced this:

- That library is ostensibly Microsoft's official library for the Microsoft Graph API. There's no published v0.2.0 or v0.3.0 (skips from v0.1.1 to v1.0.0 in a couple of months) but if it did exist, it would be over six years old.

- Was the test added by OwnCloud in a fork of the library that they didn't maintain for six years or did they ship a six year old pre-stable lib?

- They managed to expose the tests to the web (possibly the whole /vendor directory is web accessible - which would be full of plenty of other "not intended for public consumption" stuff)

- They managed to expose the tests to the web unauthenticated

- They had a test which dumped the environment

They're all so basic flaws, but they're all required. Plus you have to have creds in the environment, hence why containerised deployments are the most like affected.

That was a fascinating and well-written article and quite enjoyable reading.This is off-topic, but I'll respond briefly. I think a lot of what you're saying is true, but I disagree with assigning any blame to pilot error. What I've read (see below especially) indicates the pilots were responding as they were trained.

Anyone interested in the 737max debacle should have a look at this article.

Edit for clarification

The people who wrote the code for the original MCAS system were obviously terribly far out of their league and did not know it.

It is astounding that no one who wrote the MCAS software for the 737 Max seems even to have raised the possibility of using multiple inputs

Those lines of code were no doubt created by people at the direction of managers.

In the 737 Max case, the rules were also followed. The rules said you couldn't have a large pitch-up on power change and that an employee of the manufacturer, a DER, could sign off on whatever you came up with to prevent a pitch change on power change. The rules didn't say that the DER couldn't take the business considerations into the decision-making process. And 346 people are dead.

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.So was the vulnerability created intentionally so it could be exploited? Or was it a flaw in the code that was discovered…

Off topic, so spoilered reply:I apologize, but this Disney-vilification is oversimplifying the issues at play with the 737MAX, which bothers me enough that I am going to write a comment on the internet.

Looking deeper, why was an unsafe (in terms of redundancy) configuration available to order? You can’t spec a 737 with only one engine or one hydraulic system to save money. I put that one squarely on the manufacturer as the purchasing company’s accountants can’t be expected to evaluate safety cases, they just see extra $ on the list.So why did MCAS use just the AoA data from the captain's side, so a single failed sensor could cause these unending nose-down inputs? In short: that's how it was ordered.

Yes, but the issue here is that the MCAS failure mode did NOT present as a trim runaway. The checklists in use at the time were quite specific in the definition and trigger: “continuous uncommanded stabiliser motion”. What actually happened was intermittent nose-down input which could be countered and/or overridden by the trim switches. Given the environment this problem was presented in, which was low-level just after takeoff with very distracting false tactile and aural warnings, it is not at all surprising that a trim runaway wasn’t diagnosed as the trim was still working from a pilot PoV!Even if MCAS had its faults, the failure mode it presents as is something called "trim runaway”... ...Trim runaway is a common-enough problem that pilots are trained for it and must respond quickly.

But the software and associated processes played such a large part in this debacle, I think it is justified to apply a lot of the blame. We don’t know if better pilots could have saved the day: the same was said to begin with Sully’s ditching in the Hudson but the initial sim details were run with pilots who knew exactly what was going to happen and when. Reliability of sensors is not that much of an issue as long as you design the system to cope with an inevitable failure, which wasn’t the case here.Ultimately, pointing at MCAS and saying it is a software problem is wrong. Likewise, pointing at the pilots and saying they failed is also wrong. This was a very complex problem, and it required poor quality pilots, bad software, corporate ineptitude, dodgy companies selling pencil-whipped AoA sensors, and more to manifest itself. And, sadly it did— twice in a very short period of time.

This has to be a pretty strange set of circumstances that produced this:

- That library is ostensibly Microsoft's official library for the Microsoft Graph API. There's no published v0.2.0 or v0.3.0 (skips from v0.1.1 to v1.0.0 in a couple of months) but if it did exist, it would be over six years old.

- Was the test added by OwnCloud in a fork of the library that they didn't maintain for six years or did they ship a six year old pre-stable lib?

- They managed to expose the tests to the web (possibly the whole /vendor directory is web accessible - which would be full of plenty of other "not intended for public consumption" stuff)

- They managed to expose the tests to the web unauthenticated

- They had a test which dumped the environment

They're all so basic flaws, but they're all required. Plus you have to have creds in the environment, hence why containerised deployments are the most like affected.